The unpredictability of nature: lake Mattmark and the Saas Valley

On 14th September, the Mattmark 1965 memorial half-marathon takes place in memory of the glacier collapse of 30th August 1965. 88 people died that day. But the story goes way back.

The catastrophe of 1965 is not the only disaster the Allalin Glacier has seen. Its wild and unpredictable nature has repeatedly threatened the existence of the Saas population. The glacier originates on the 4,190-metre-high Strahlhorn, which, along with the Allalinhorn, the Alphubel, and the Rimpfischhorn, belongs to the Allalin group.

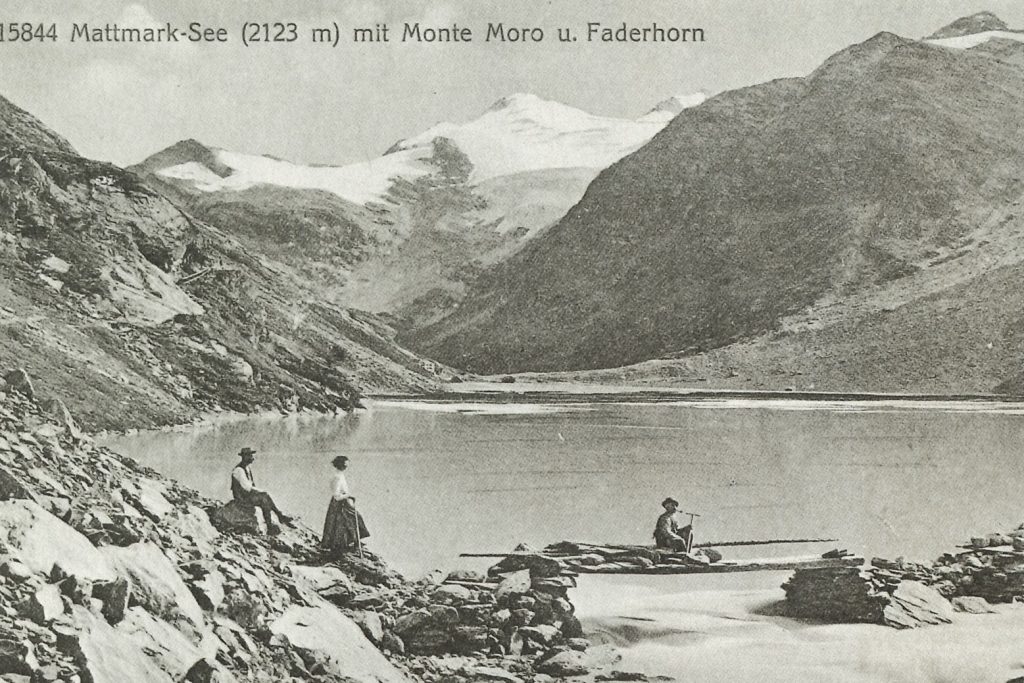

Ice, an unreliable dam

From the 15th century to the beginning of the 20th, a period known as the Little Ice Age, the Allalin glacier repeatedly grew and receded. As it grew time and time again it filled the entire valley through which the Saaser Vispa ran, and dammed the river as a result. When the ice barrier melted, however, the glacial lake behind it would flood the Saas Valley. 26 such floods have been recorded. The sand and gravel sediment left behind turned invaluable farmland into quasi-deserts for years afterwards, forcing parts of the Saas population to emigrate.

In ‘The Chronicle of the Saas Valley’ (Die Chronik des Thales Saas), published in 1851, cleric Peter Joseph Ruppen recorded particularly bad flash floods in 1633, 1680 and 1772. 1633 and 1680 were reported to be particularly devastating years.

Devastation in the valley

The destruction caused by the Allalin glacier was such that contemporary author Otto Supersaxo christened it the “dragon” on the Mattmark valley floor. The Saas population had bounced back from natural disasters like avalanches and landslides, again and again, making their peace with what nature threw at them and eking out a modest life through hard work. But the lake Mattmark “tsunami” of 4th August 1633 shook the population to its core. Boulder and debris-laden water tore through the valley all the way down to Visp, devastating farmland in its path. Rocks and sand-covered pastures, fields and even houses were submerged deep below the water’s surface. Sources vary, but it’s thought that around 750 Saas Valley dwellers gave up everything and emigrated en-masse. At the time, that was between a third and a half of the population.

“Traumatized by the devastation, the

remaining population swore not to

play, dance or celebrate for

the next 40 years.”

Those who remained faced years of work to reclaim the land. Singletons vowed not to marry until the work was completed. True to their word, there wasn’t a single wedding in the Saas parish district for the next 14 years. But in 1680, the horror repeated itself. This time around, flash flooding even destroyed 18 houses in Visp. Traumatized by the devastation, the remaining population swore not to play, dance, or celebrate for the next 40 years, a vow was recorded by notary Peter Anthamatten on 14th July, 1680.

Sure enough, the dragon remained dormant for almost a whole century after that. Then, on 17th September 1772, following two days of heavy rain, the beast awoke and the lake’s waters burst through the glacier wall, once more causing flooding and destruction down the valley.

Early attempts to tame the dragon

In 1833, lake Mattmark was again threatening to burst its banks. This time, the Saas population received 200 francs (equivalent to about 4000 Swiss francs today) from the government to create a six-shoe-deep spillway (1 shoe equals 29.326 centimetres). Just one year later the lake broke through again, washing away nine bridges in the valley. 1834 saw a pathway drilled through the Allalin glacier allowing the dammed water to flow at a manageable rate. But this solution didn’t last long: in 1837 the Mattmark dragon flexed its muscles yet again, with the water building up to unmanageable levels and breaking through once more.

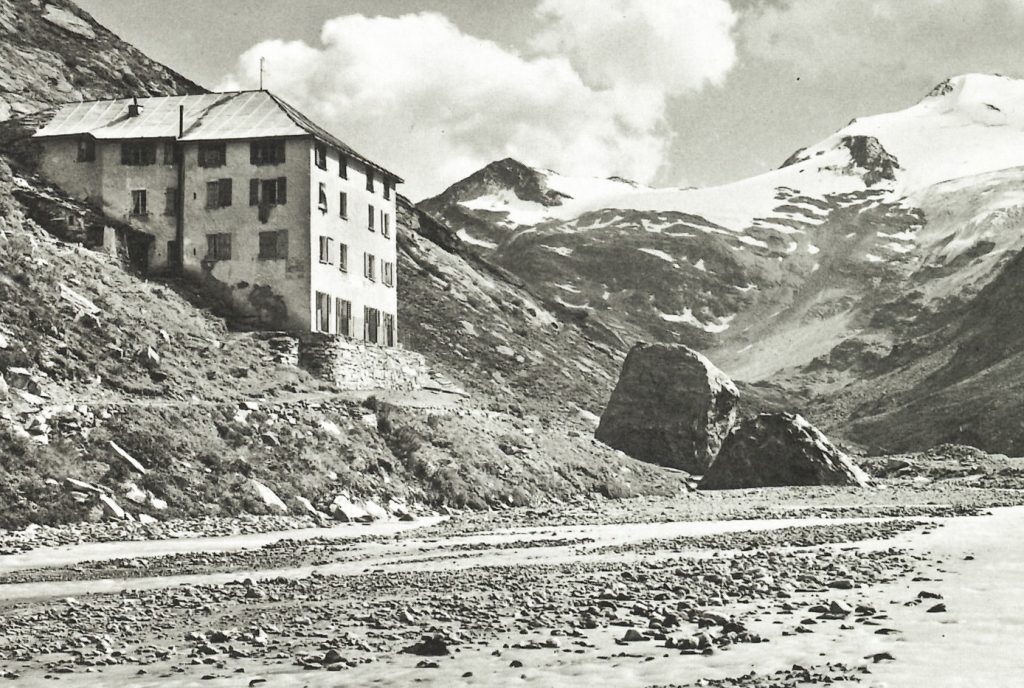

Dramatic fluctuations in water level during the 1840s finally clogged the drainage channel. In 1846 the state experimented with using wooden channels to direct water into the glacier’s crevasses, without success. On 24th September 1920, lake Mattmark flooded Saas-Almagell once again, and large areas of cultivated land were destroyed, along with Hotel Portjengrat.

Building the Mattmark dam

In 1960, Kraftwerke Mattmark AG finally started construction of the present Mattmark dam. Five years later, without warning, the dragon struck from above. At twenty past five on 30th August 1965, a huge piece of the Allalin glacier’s ice tongue collapsed. The falling ice destroyed the residential barracks, offices and site canteen below. Eighty-six men and two women were buried under two million cubic meters of ice and scree, 11 more were injured. The majority were construction workers, a combination of Italians and Swiss and the recovery of the 88 bodies took many months.

Since 1965, there have been no more incidents. The dragon has been well controlled since the dam was constructed.

Mattmark 1965 memorial half-marathon

The start point of the memorial race is the round church in Saas-Balen, from where this 21.1 kilometre half-marathon leads through glorious larch forests past Saas-Grund. The race continues through Saas-Almagell to the hamlet of Zer Meiggeru, from which point it follows the old road as it continues upwards towards the dam. The last part of the route is the most enjoyable for the runners, boasting eight kilometres of practically flat terrain around the picturesque lake Mattmark.

Those who prefer a less strenuous challenge can take on just the final section around the lake, or sign up for the Nordic Walking/Fun category. There’s also a children‘s race along the dam wall.

“More than 300 valley dwellers lost all their belongings as a result of the flash flood on 4th August 1663.”